Carbon-Neutral Packaging: The Truth Behind Offsetting and Real Sustainability

There’s a comforting simplicity to the phrase carbon neutral. It conjures an image of balance — of every emission neatly canceled out somewhere else, of a clean slate written in the language of sustainability.

For many companies, this label has become the ultimate environmental badge of honor, appearing on everything from airline tickets to packaging tape. Yet beneath the tidy arithmetic lies a more troubling truth: carbon neutrality, as it’s often practiced, is more illusion than solution.

In 2023, more than 1,500 global brands publicly claimed to have achieved or were pursuing carbon neutrality, according to Carbon Market Watch. But a detailed review by the organization found that most of these claims lacked verifiable proof of genuine emission reductions. Many relied heavily on offsetting schemes — paying for tree planting or renewable energy projects — that often fail to deliver the promised climate benefits.

A 2022 investigation by The Guardian, Die Zeit, and SourceMaterial revealed that over 90% of rainforest carbon offsets certified by Verra were essentially worthless, having no measurable impact on reducing atmospheric carbon.

The problem isn’t in the intention to act, but in the illusion of completion. Offsetting allows companies to buy their way to neutrality without changing the processes that cause emissions in the first place. It’s a form of environmental outsourcing — a transaction that converts moral responsibility into financial abstraction. The UK’s DEFRA warns that carbon neutrality labels “can be misleading if used without clear disclosure of scope and methodology,” echoing the Carbon Trust’s recommendation that “real net zero” requires measurable reduction across the entire value chain, not merely compensation through credits.

Packaging sits at the heart of this debate. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates that packaging accounts for nearly 36% of global plastic production, and a significant portion of lifecycle carbon emissions. Declaring a “carbon-neutral box” while sourcing virgin materials or relying on fossil-based logistics is like claiming a diet’s success because someone else skipped dessert.

The Carbon Footprint of Packaging

If “carbon neutrality” is the story we tell ourselves about balance, then the carbon footprint of packaging is the story of everything that comes before — and after — a product is wrapped, shipped, and discarded. To understand what “real sustainability” means in packaging, we must first trace the invisible trail of emissions that follows every box, bottle, and film from its birth to its end. Only then can procurement leaders and sustainability officers distinguish between genuine progress and cosmetic change.

1. The Anatomy of a Footprint

Every packaging material, whether it’s corrugated cardboard, polyethylene film, or a sleek bioplastic pouch, carries a carbon cost embedded in its lifecycle. The Carbon Trust defines this as the “cradle-to-grave” assessment: emissions generated during raw material extraction, manufacturing, transport, use, and disposal. These emissions are typically measured in kilograms of CO₂ equivalent (CO₂e) per kilogram of packaging.

But what makes packaging such a significant contributor to global carbon output? The answer lies in its ubiquity and disposability. According to WRAP UK, the packaging sector accounts for around 2% of total UK greenhouse gas emissions, with the majority arising during material production and end-of-life management. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation places global packaging-related emissions closer to 5% of all anthropogenic CO₂, a staggering figure considering much of it is single-use.

2. Materials: Where Emissions Begin

The carbon story begins long before the packaging line.

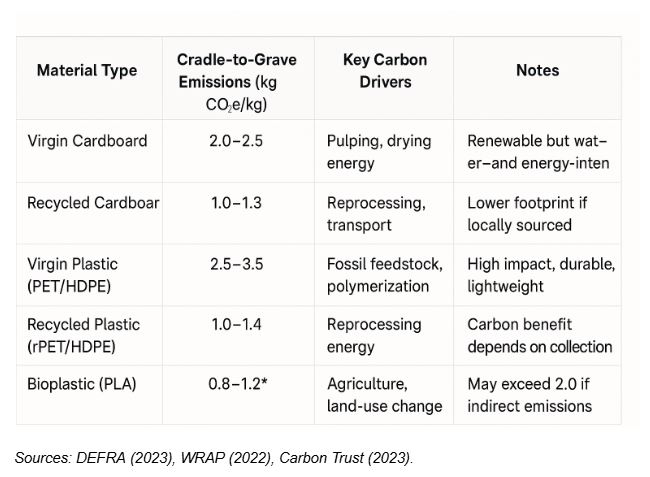

Cardboard is often perceived as a “green” material because it’s recyclable and derived from renewable resources. However, DEFRA’s 2023 Packaging Waste Report shows that virgin cardboard production emits roughly 1.7–2.5 kg CO₂e per kilogram due to energy-intensive pulping and drying processes. Recycled cardboard performs better — cutting emissions by up to 50% — but the benefit diminishes if recycled fibers travel long distances for processing. Moisture content, fibre degradation, and contamination can also reduce recyclability and extend the lifecycle emissions per box.

Plastics, on the other hand, remain both the villain and the workhorse of modern packaging. Virgin PET (polyethylene terephthalate) or HDPE (high-density polyethylene) can emit between 2.5–3.5 kg CO₂e per kilogram, according to WRAP’s Plastic Footprint Study (2022). That figure is primarily driven by fossil fuel feedstocks and the high energy demands of polymerization. However, recycled polymers — known as rPET or rHDPE — can cut this impact by nearly 60–70%, provided collection and reprocessing systems are efficient.

Then there’s bioplastics, marketed as the miracle fix. Materials like PLA (polylactic acid) are derived from plant sources, often corn or sugarcane, and can emit as little as 0.8–1.2 kg CO₂e per kilogram during production. Yet that headline number hides complexity. Bioplastics require agricultural inputs — fertilizers, irrigation, and land use — which contribute to indirect emissions. The Carbon Trust cautions that when land-use change is included, total emissions can rival or even exceed those of conventional plastics. Moreover, most bioplastics are not biodegradable in natural environments, requiring industrial composting facilities that remain rare across the UK and EU.

In short, the material with the lowest “factory gate” footprint is not always the most sustainable once the full system is considered.

3. Production and Conversion: The Energy Equation

After raw materials are sourced, the conversion process — forming, printing, laminating, and sealing — adds another layer of emissions. Manufacturing energy typically represents 10–20% of total lifecycle CO₂, depending on efficiency and energy mix.

A DEFRA analysis (2023) found that for a standard corrugated box, roughly 0.5 kg CO₂e arises from the converting process alone. Plastic films fare worse if production relies on grid electricity derived from fossil fuels. In contrast, packaging manufacturers using on-site renewable energy or energy recovery systems can reduce this footprint significantly.

This is where procurement decisions ripple outward. Choosing suppliers aligned with Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) commitments or ISO 14064-certified processes can cut embodied carbon before a single product is packed. Yet such decisions demand transparent lifecycle data — something still lacking in much of the global packaging supply chain.

4. Logistics: The Invisible Miles

Even the greenest material loses its advantage if it travels halfway around the world. Transport contributes between 5–15% of total packaging-related emissions, depending on mode and distance.

For instance, WRAP’s comparative study of packaging distribution (2022) found that importing recycled polymer pellets from Asia to the UK could add up to 0.3 kg CO₂e per kilogram, effectively erasing the carbon savings of recycling. Similarly, lightweight bioplastic pouches might reduce freight emissions per unit but require more protective outer packaging, offsetting the benefit.

Domestic sourcing — a strategy increasingly favoured by Allpack UK and other sustainability-driven suppliers — can reduce emissions through shorter supply chains and consolidated shipments. The Carbon Trust recommends “in-region circularity” as a best practice: keeping materials within the same geographic loop from production to reuse or recycling.

5. Use Phase: The Hidden Durability Factor

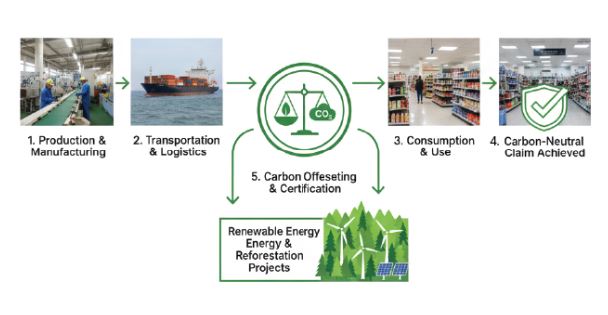

While most packaging is single-use, the “use phase” still matters. Reusable systems — from heavy-duty polymer crates to collapsible pallets — distribute their carbon cost across multiple cycles. According to WRAP’s Reusable Packaging Framework, a reusable container needs 5–15 rotations to outperform its single-use counterpart in carbon terms. But that benefit depends on efficient return logistics and cleaning methods powered by low-carbon energy.

This is where design for reuse intersects with design for logistics. Lighter, modular, and stackable solutions can dramatically reduce both transport emissions and breakage rates, providing dual sustainability benefits.

6. End-of-Life: The Fork in the Road

The final act in packaging’s carbon story is often the most misunderstood. The end-of-life stage — recycling, composting, incineration, or landfill — determines whether the carbon loop closes or leaks.

- Cardboard boasts the highest recovery rate in the UK, at around 80%, but contamination and fibre degradation reduce circularity. Recycling one tonne of cardboard saves about 1.5 tonnes of CO₂e compared to landfilling, according to DEFRA.

- Plastic packaging remains the laggard. Only 46% of plastic waste in the UK is recycled, and a large share is exported, often to countries lacking robust environmental controls. Incineration with energy recovery offsets some fossil fuel use, but emits around 1.7 kg CO₂e per kilogram of plastic burned (WRAP, 2022).

- Bioplastics, while compostable in theory, rarely end up in industrial composting facilities. When landfilled, they behave much like conventional plastics; when incinerated, they release nearly equivalent carbon.

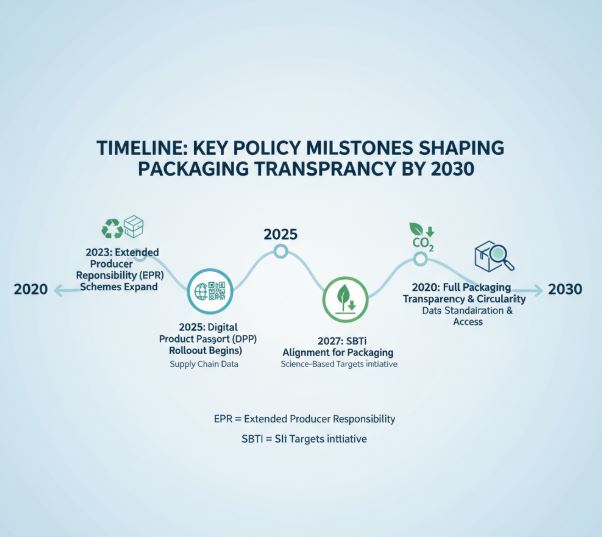

This is where policy and infrastructure become as critical as product design. The UK’s Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework, rolling out through 2025, aims to internalize these end-of-life costs, forcing brands to account for the full carbon impact of their packaging choices.

7. Comparing the Contenders

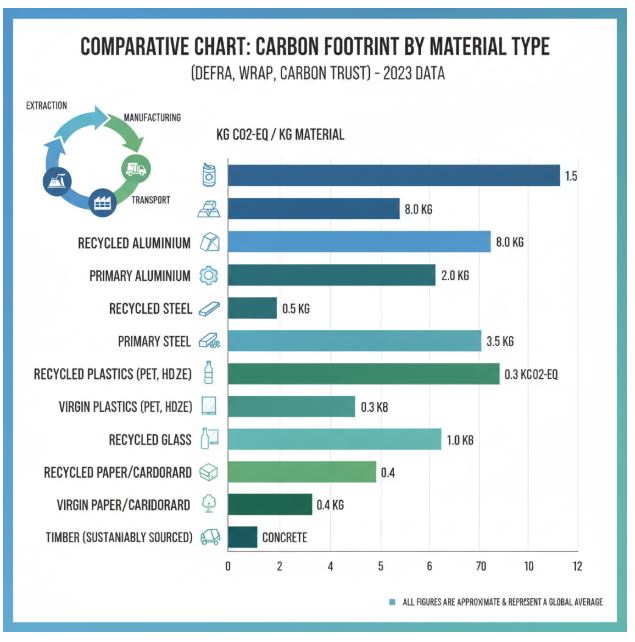

To see how these factors stack up, consider three simplified lifecycle scenarios for 1 kilogram of packaging material used in the UK:

Sources: DEFRA (2023), WRAP (2022), Carbon Trust (2023).

This table underscores a central truth: context determines carbon. A recycled polymer produced in the UK can outperform a bioplastic imported from overseas. Likewise, a lightweight corrugated box may carry a smaller footprint than a compostable pouch if reused or efficiently recycled.

8. From Measurement to Meaning

Understanding these footprints isn’t just an academic exercise — it’s a leadership imperative. Procurement teams equipped with verified carbon data can make choices that align cost efficiency with climate responsibility. Frameworks such as PAS 2050, GHG Protocol Product Standard, and ISO 14067 provide methodologies for lifecycle carbon assessment. Yet, as the Carbon Trust notes, “data is not enough without decisions.”

The challenge is not to find a perfect material but to design systems that minimize emissions through every stage of the lifecycle. That means integrating circular design, investing in low-carbon logistics, and building partnerships that prioritize reduction over offsetting.

As this analysis shows, there’s no such thing as zero-carbon packaging — only packaging that’s on a genuine path toward less.

This raises the central question for the sustainability-minded procurement leader: are we truly reducing emissions, or simply relocating them? The future of sustainable packaging demands not neutrality, but accountability — a shift from transactional offsetting to transformational design, from symbolic gestures to measurable change.

Offsetting Explained — and Why It’s Not Enough

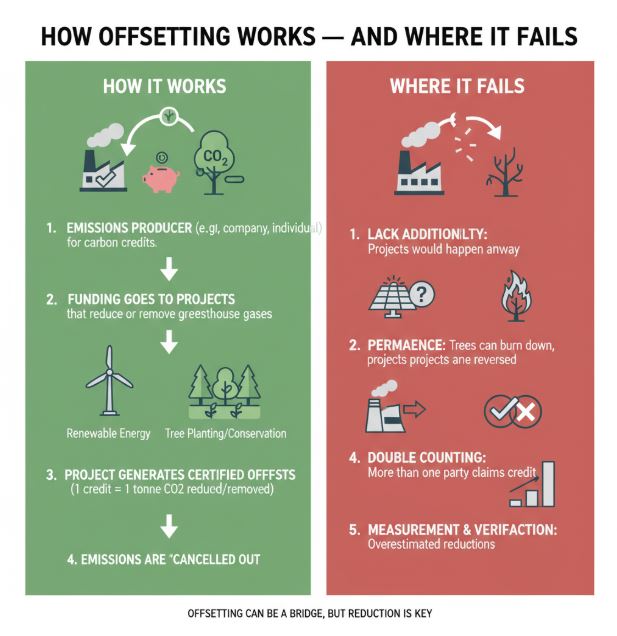

At first glance, carbon offsetting seems like a tidy moral equation: if you emit a tonne of carbon here, you pay for a project that saves or absorbs a tonne of carbon somewhere else. The logic appeals to our sense of symmetry — a global bookkeeping system that allows business as usual, so long as the sums add up to zero. But as Carbon Market Watch and The Gold Standard Foundation have repeatedly shown, the math behind this moral ledger rarely balances in reality. Offsetting, for all its good intentions, too often postpones the harder work of cutting emissions at their source.

1. What Carbon Offsetting Is — and How It’s Supposed to Work

Carbon offsetting emerged in the 1990s as part of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) efforts to curb global warming. Under mechanisms such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), companies and nations could compensate for their greenhouse gas emissions by investing in projects that claimed to reduce emissions elsewhere — from reforestation and renewable energy installations to methane capture and cookstove distribution.

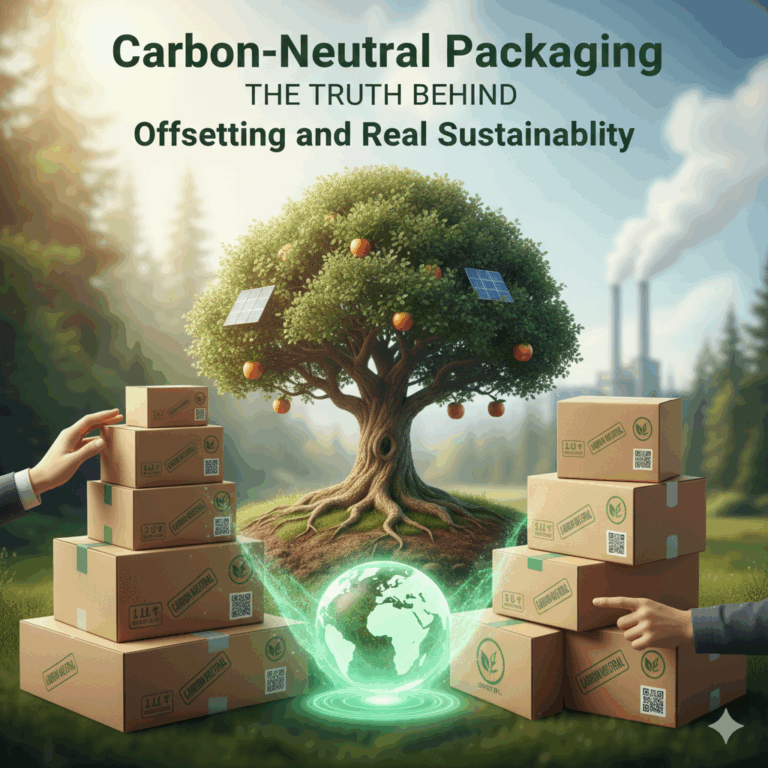

In principle, the system works like this:

- A project developer (say, a forest conservation NGO or renewable energy firm) estimates the emissions reduction their project will achieve compared to a “business-as-usual” baseline.

- A verifier audits this claim.

- The project is issued carbon credits, each representing one tonne of CO₂ avoided or removed.

- Companies or individuals buy those credits to “offset” their own emissions, theoretically bringing their net impact to zero.

When done rigorously, offsets can fund valuable projects that improve biodiversity, create jobs, or accelerate clean energy transitions. Frameworks such as The Gold Standard and Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) were established to ensure integrity, transparency, and traceability.

Yet the offset market has been plagued by inconsistency, opacity, and exaggeration — problems so pervasive that the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) is now rewriting the rules for what qualifies as a “high-quality” credit.

2. The Flaws in the System

- The Baseline Problem

Offsets depend on estimating what would have happened without the project — a counterfactual that can never be truly verified. This creates vast room for manipulation. A forest protection project, for instance, might claim to “avoid” deforestation that was never realistically at risk, issuing credits for imaginary savings.

A 2023 joint investigation by The Guardian, Die Zeit, and SourceMaterial found that over 90% of rainforest carbon offsets approved by Verra, one of the largest certifiers, were essentially worthless. The forests in question were not facing significant deforestation threats, meaning the claimed “savings” did not actually exist.

- Permanence and Leakage

Even when carbon is genuinely sequestered, it may not stay that way. A forest can burn, a soil carbon project can erode, and a mangrove restoration site can be uprooted by future development. These reversals re-release carbon that was once “offset.” In 2022, wildfires in the U.S. Pacific Northwest wiped out thousands of hectares of offset forests, effectively erasing millions of tonnes of supposed sequestration.

Carbon Market Watch notes that such risks make biological offsets inherently temporary — a fragile promise of storage in a volatile world. In contrast, emissions from burning fossil fuels are permanent; once CO₂ is in the atmosphere, it can persist for centuries.

- Additionality — The Core Integrity Test

To count as an offset, a project must deliver emissions reductions beyond what would have occurred otherwise. But many renewable energy or efficiency projects today would have happened anyway due to falling technology costs and government incentives. Gold Standard’s 2023 Review found that up to 40% of projects failed to meet this “additionality” criterion, meaning their claimed benefits were not truly incremental. - Double Counting and Transparency

The global offset market — valued at over $2 billion annually — is riddled with double counting. Credits are sometimes sold multiple times or counted simultaneously by both the project host country and the buyer company. Despite the UN’s Article 6.4 mechanism under the Paris Agreement aiming to prevent this, enforcement remains weak.

In short, offsetting’s moral simplicity hides an operational mess. It’s like paying someone else to diet for you — admirable in intent, but the mirror won’t lie.

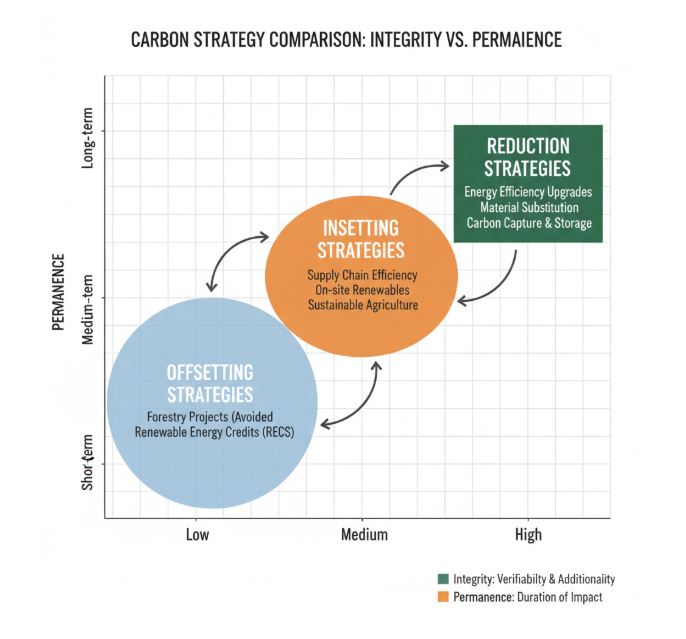

3. Offsetting vs. Insetting vs. Reduction

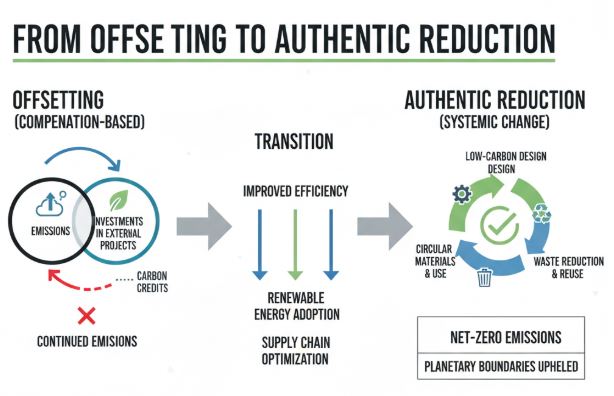

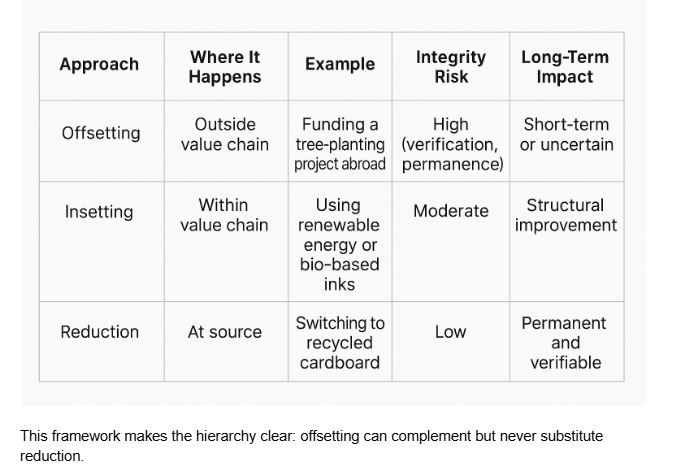

If offsetting represents outsourcing responsibility, insetting and reduction represent bringing it home.

Offsetting happens outside a company’s direct operations or value chain. A packaging manufacturer in the UK might buy credits from a reforestation project in Kenya. The emissions continue locally; the “solution” happens elsewhere.

Insetting, by contrast, refers to emission reduction or removal projects within a company’s own value chain — such as switching to renewable electricity in its production facilities, improving transport logistics, or supporting regenerative agriculture among suppliers. The International Platform for Insetting (IPI) defines it as “a strategy to create measurable climate impact within the sphere of a company’s influence.”

Finally, reduction — the gold standard of sustainability — means eliminating or avoiding emissions altogether. This could involve lightweighting packaging, redesigning materials, sourcing recycled inputs, or electrifying fleets. Unlike offsetting, reduction alters the system rather than compensating for it.

Here’s how they compare in terms of integrity and impact:

This framework makes the hierarchy clear: offsetting can complement but never substitute reduction.

4. The False Comfort of “Carbon Neutral” Labels

The growth of offsetting has spawned a booming “carbon-neutral certification” industry. Labels such as Climate Neutral Certified or CarbonNeutral® offer companies the ability to claim neutrality through a mix of reduction and offsetting. But even here, transparency varies widely.

The Carbon Trust, one of the UK’s most respected verification bodies, distinguishes between carbon neutral (where emissions are offset) and net zero (where emissions are cut to near-zero before limited, high-quality offsets are used). In practice, however, many brands blur this line.

A 2022 European Commission investigation found that half of all “carbon neutral” claims lacked adequate evidence or overstated their scope. This has prompted growing regulatory scrutiny. The EU’s Green Claims Directive, expected to take effect by 2026, will require companies to substantiate environmental claims with verifiable lifecycle data and third-party audits.

For procurement and sustainability officers, the message is clear: in the coming years, offsetting alone will no longer satisfy compliance or credibility.

5. The Case for Real Reduction — and Responsible Offsetting

The future of climate accountability lies not in abandoning offsetting altogether, but in repositioning it as a last resort, not a first response. The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) outlines a clear sequence:

- Measure emissions accurately.

- Reduce within your operations and supply chain using proven strategies.

- Neutralize only residual emissions through verified, high-quality offsets that prioritize permanence, additionality, and co-benefits.

When used responsibly, offsetting can support genuine climate action — funding forest conservation or carbon removal technologies like biochar, direct air capture, or enhanced rock weathering. The difference lies in accountability. A company should never buy offsets to appear neutral but to take responsibility for what it cannot yet eliminate.

The Gold Standard and Carbon Market Watch both advocate for a transition from “credit-based” to “impact-based” climate finance — meaning investments should focus on measurable ecosystem and community benefits rather than symbolic carbon arithmetic.

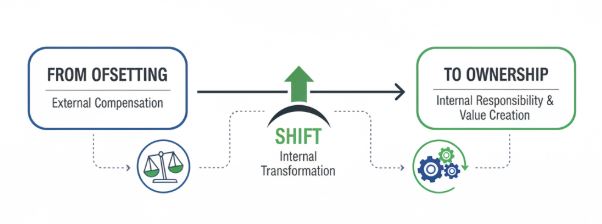

6. Reframing Leadership: From Offsetting to Ownership

Simon Sinek once wrote that leadership is not about being in charge but about taking care of those in your charge. The same applies to sustainability leadership. The question is not “How can we erase our emissions on paper?” but “How can we design systems that no longer require erasure?”

That’s the pivot point for modern packaging companies. Instead of outsourcing responsibility to distant forests, they can decarbonize through material innovation, circular logistics, and renewable manufacturing. Offsetting should evolve into investment in regeneration — not as a license to emit, but as a commitment to restore.

This moral and strategic shift will define the next decade of corporate climate action. Companies that embrace genuine reduction and insetting will not only future-proof their operations but also earn the trust of consumers, investors, and regulators alike.

As Carbon Market Watch succinctly put it, “Offsets can be part of the toolbox, but they cannot build the house.”

7. Toward a New Standard of Accountability

The path forward requires rigorous disclosure, credible metrics, and an honest conversation about what progress really means. That means:

- Prioritizing verified reduction across Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions.

- Investing in insetting projects that strengthen local resilience.

- Using offsets only for residual emissions that cannot yet be abated.

- Reporting transparently under standards such as TCFD and SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard.

In a marketplace saturated with “carbon-neutral” claims, the true differentiator will be authenticity. Companies that acknowledge the limits of offsetting — and move decisively toward measurable, science-based reduction — will not just meet compliance; they’ll lead it.

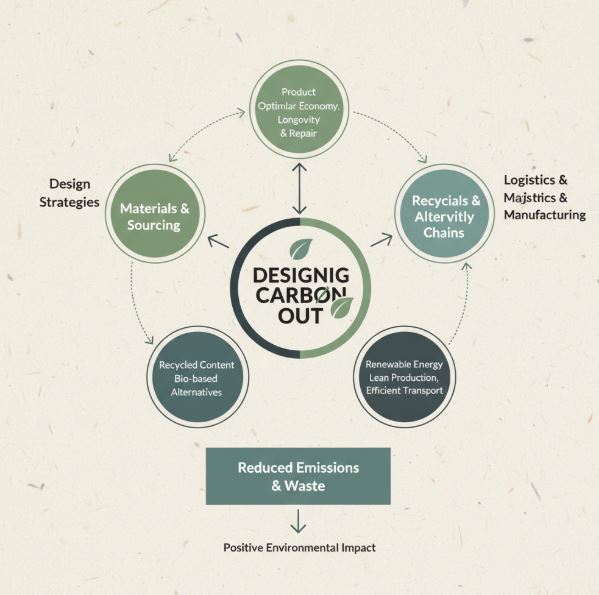

Designing for Reduction — The Real Sustainability Strategy

If offsetting is the illusion of balance, designing for reduction is the reality of progress. It’s the moment when sustainability stops being a marketing claim and becomes an engineering principle — built into every millimetre of cardboard, every pallet configuration, every material decision. For procurement leaders and sustainability officers, this is where the path to net zero begins: not in buying carbon credits, but in designing carbon out of the system.

Reduction is not glamorous; it’s granular. It happens in quiet decisions — the shape of a box, the density of a polymer, the automation behind a fulfilment line. Yet these micro-decisions accumulate into the macro-impact that defines a company’s climate integrity. The Carbon Trust and WRAP UK both identify packaging design as one of the most immediate levers for emission reduction across supply chains.

1. Right-Sizing and Material Efficiency

Perhaps the simplest, yet most overlooked, form of carbon reduction is using less. Over-packaging is an industry habit rooted in caution — the fear of damage and the illusion of premium presentation. But every unnecessary cubic centimetre translates into excess weight, wasted material, and higher transport emissions.

Right-sizing uses data-driven packaging design to ensure products fit their containers with minimal void space. When implemented at scale, the results are transformative. A 2023 WRAP case study showed that optimizing box dimensions across a UK e-commerce retailer reduced packaging volume by 22% and saved 1,200 tonnes of CO₂e annually, simply by eliminating air and filler material.

Similarly, automated box-on-demand systems — like those used in modern fulfilment centres — cut down corrugate use by up to 30% while reducing storage space and logistics inefficiencies. In other words, smarter packaging can mean smaller footprints, literally and environmentally.

2. Recycled and Renewable Materials

The next layer of design reduction lies in material substitution — replacing virgin resources with recycled or renewable alternatives that carry lower embodied carbon.

- Recycled Paper and Cardboard: Each tonne of recycled cardboard saves about 1.5 tonnes of CO₂e compared to virgin fibre production (DEFRA, 2023). It also requires 70% less energy and 50% less water, according to WRAP. The key challenge is maintaining performance — ensuring recycled materials retain compression strength and moisture resistance. Advances in fibre reinforcement and water-based coatings now make this increasingly feasible for even demanding supply chains.

- Recycled Plastics: Transitioning from virgin to rPET or rLDPE can reduce carbon impact by 60–70%, provided the recycling streams are well managed. UK initiatives such as the Plastics Pact have accelerated the use of closed-loop systems, where waste from consumer packaging is reprocessed into new films and trays.

- Bio-based and Hybrid Solutions: Innovations in plant-based polymers, paper-plastic hybrids, and compostable coatings are further diversifying low-carbon packaging options. However, as the Carbon Trust warns, bio-based doesn’t automatically mean low-carbon. True sustainability comes from full lifecycle verification — factoring in agricultural emissions, transport, and end-of-life outcomes.

Allpack UK, among others in the industry, has focused on sourcing certified recycled and FSC®-approved materials, aligning with both ISO 14001 environmental management systems and the principles of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s circular economy framework.

3. Automation and Digital Optimization

Reducing emissions isn’t only about materials — it’s about systems efficiency. Packaging automation and digitalization are emerging as key frontiers in low-carbon operations.

Automated packing lines can reduce material waste by precisely measuring each product and cutting packaging to fit. This not only saves on materials but reduces labour energy use and error rates. According to WRAP’s 2022 Packaging Efficiency Report, factories that adopted automated right-sizing and tape application saw a 15–25% decrease in energy consumption compared to manual lines.

Meanwhile, digital twins — virtual models of supply chain operations — allow companies to simulate packaging scenarios and identify carbon hotspots before making physical changes. Paired with IoT sensors and AI-driven logistics software, these systems can fine-tune packaging density, optimize pallet loads, and minimize transport miles — turning sustainability into a quantifiable, repeatable process.

Automation is not just a cost-saving tool; it’s a carbon-saving one. It eliminates inefficiencies that human intuition alone cannot detect, replacing guesswork with precision.

4. Circular Supply Chains and EPR Readiness

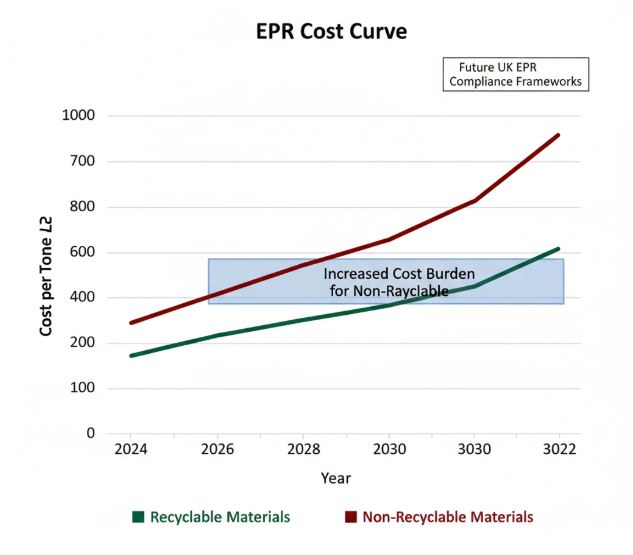

One of the defining shifts in sustainability leadership is the move from linear to circular supply chains, where packaging materials are reused, recycled, or repurposed rather than discarded. The UK’s forthcoming Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework — set for full implementation by 2025 — will make this transformation unavoidable.

Under EPR, producers will bear the full cost of packaging waste management, including collection, recycling, and disposal. In practice, this means every gram of packaging will carry a price tag tied to its recyclability and environmental performance. Companies that design for reduction today will be economically rewarded tomorrow.

For example, packaging that is easily separable, mono-material, or clearly labelled for recycling will incur lower compliance costs under EPR. Conversely, complex laminates and non-recyclable films will become financial liabilities.

Circularity also means designing for reuse. Reusable transit packaging — such as durable polymer crates and returnable pallets — can reduce lifecycle emissions by up to 80% over single-use equivalents once reused 10–15 cycles (WRAP, 2023). The challenge lies in building the logistics infrastructure to recover and recirculate these assets efficiently — something automation and data tracking can greatly assist.

5. Collaboration Across the Value Chain

True reduction is a collective act. Packaging manufacturers, suppliers, and brand owners must collaborate to align on verified carbon data and design standards. The Carbon Trust’s Route to Net Zero framework emphasizes that more than 70% of corporate emissions occur in Scope 3 — outside direct control, often within packaging and logistics.

That means partnerships matter. Working with certified suppliers, sharing LCA data, and setting joint Science-Based Targets (SBTi) are all ways to accelerate system-level change. Retailers like Tesco and Unilever have already begun publishing supplier scorecards linking procurement contracts to emission reduction performance — a trend that will soon define the entire packaging market.

6. From Compliance to Competitive Advantage

Designing for reduction is more than regulatory preparation — it’s strategic leadership. Companies that engineer sustainability into their packaging not only cut emissions but also unlock commercial benefits: lower material costs, reduced freight expenses, enhanced brand reputation, and resilience in a carbon-constrained future.

A study by McKinsey & Company (2023) found that firms integrating sustainability-led design achieved average cost savings of 10–20% per unit of packaging and a 30% faster response time to evolving regulations. In short, reduction pays back — in both environmental and economic capital.

The shift to design-led decarbonization is already underway. Allpack UK’s approach — combining lifecycle assessments, material innovation, and automation — demonstrates what the future of packaging looks like when sustainability becomes structural, not superficial.

Reduction is not the final stage of sustainability; it’s the foundation. The companies that master it today will define the standards for tomorrow.

The Future of Carbon Accountability in Packaging

For years, sustainability claims have relied on good intentions and glossy reports. But the future of packaging — and indeed, of credible corporate climate action — will be built on something far more concrete: traceable, verifiable carbon data. The era of vague “eco-friendly” labels is ending. What comes next is accountability — measured not in slogans, but in grams of CO₂.

1. The Rise of Traceable Carbon Data

The shift toward traceable carbon metrics marks a profound cultural change in packaging. No longer can companies rely on generic averages or offset certificates to prove their climate performance. Increasingly, regulators, investors, and customers demand product-level transparency: how much carbon was emitted in making this box, film, or label — and where exactly those emissions occurred.

Initiatives like the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), and GHG Protocol Product Standard are establishing common frameworks for Scope 3 measurement — capturing emissions embedded across the entire value chain. This means carbon data must now flow with materials, not just with invoices.

For example, the Carbon Trust’s Route to Net Zero Standard encourages companies to track and verify emissions from raw materials through end-of-life. That requires digital infrastructure — cloud-based LCA (Life Cycle Assessment) tools, AI-driven analytics, and standardized reporting formats. The goal is a world where every packaging component carries its carbon story as clearly as its barcode.

2. Digital Product Passports: Packaging’s Transparency Revolution

By 2030, that world may be here. The European Commission’s Digital Product Passport (DPP) initiative — part of the EU Circular Economy Action Plan — will make traceability a legal requirement for many product categories, including packaging.

A Digital Product Passport is a secure, scannable record containing verified information about a product’s composition, origin, carbon footprint, and recyclability. It links physical materials to digital data, enabling everyone — from manufacturers to consumers — to see how sustainable a product truly is.

Imagine scanning a parcel’s label and instantly seeing its lifecycle carbon emissions, recycled content percentage, and end-of-life options. For procurement teams, this means better decision-making; for regulators, better oversight; and for consumers, genuine empowerment.

In the UK, WRAP and DEFRA are already exploring how DPPs could align with the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) system and Plastic Packaging Tax. When combined, these policies will form a web of accountability — one that rewards transparency and penalizes opacity.

But implementing such systems will require more than compliance — it will require collaboration. To make digital traceability work, every supplier, converter, and logistics partner must contribute verified data. That’s where blockchain technology and digital twins are beginning to play a transformative role, allowing immutable, real-time tracking of emissions and material flows across the value chain.

3. Verified Transparency as a Competitive Advantage

Accountability is no longer just a regulatory necessity; it’s becoming a market differentiator. Companies that can prove their emission reductions will command trust — from investors seeking ESG resilience to customers choosing authentic sustainability over empty claims.

Take the example of packaging firms partnering with GS1 UK, the global data standards organization, to embed unique digital identifiers in every SKU. These identifiers can link to certified carbon data verified under ISO 14067 or PAS 2060, allowing instant validation of carbon claims. The result is not only transparency but traceability with integrity — a chain of custody for climate impact.

As Carbon Market Watch has argued, “What gets measured gets managed; what gets verified gets trusted.” This simple truth underpins the next phase of packaging innovation: the alignment of technology, regulation, and leadership around shared climate goals.

4. Leadership Beyond Compliance

Yet, numbers alone won’t define the future — purpose will. Real sustainability leadership is not about chasing certifications; it’s about reshaping systems so that reducing carbon becomes the natural outcome of doing business responsibly. That means designing packaging for circularity, investing in renewable operations, and setting science-based targets that extend beyond the factory floor.

Simon Sinek reminds us that leadership begins with why. The “why” for packaging companies today is larger than carbon metrics — it’s about ensuring that every design choice contributes to a livable planet. That requires moral clarity, not just technical proficiency.

In the coming decade, carbon accountability will evolve from reporting to responsibility. Data will replace declarations; transparency will replace trust as the currency of credibility. Companies that lead this transition — those who measure honestly, act decisively, and collaborate openly — will not only meet the demands of regulators but inspire the confidence of the marketplace.

The packaging industry’s greatest innovation won’t be a new material or machine. It will be a new mindset — one where carbon transparency is as fundamental as safety and quality, and where sustainability isn’t a department, but a shared purpose.

Because in the end, the question is no longer how green we look — but how accountable we are.

References & Useful Sources

- Carbon Trust – Route to Net Zero Standard

The Carbon Trust’s official page describing its Route to Net Zero Standard, including verification tiers and its role in helping organisations plan and certify emissions reductions.

https://www.carbontrust.com/what-we-do/net-zero-transition-planning-and-delivery/route-to-net-zero-standard Carbon Trust - Carbon Trust – Launch Announcement for Route to Net Zero

A press-release describing how the Route to Net Zero Standard supports companies’ climate ambitions, aligning with science-based targets. https://www.carbontrust.com/news-and-insights/news/the-carbon-trust-launches-new-route-to-net-zero-standard-certifying-the-journey-to-climate-leadership Carbon Trust - Carbon Trust – “A guide to Net Zero for businesses”

A downloadable guide explaining net zero concepts, target-setting, and the Route to Net Zero Standard.

https://ctprodstorageaccountp.blob.core.windows.net/prod-drupal-files/documents/resource/restricted/A_guide_to_Net_Zero_for_businesses.pdf CTProdStorageAccountP - DEFRA / UK Government – “Unlocking Resource Efficiency: Phase 2 Plastics Report”

A recent UK Government / DEFRA-commissioned report exploring plastics resource efficiency, recycling projections, and emissions.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6620f183651136bd0b757d84/unlocking-resource-efficiency-phase-2-plastics-report.pdf GOV.UK - WRAP – UK Plastics Pact / WRAP Annual Reports

WRAP’s public reports include progress, metrics, and case studies on plastics, packaging, recycling, and circular economy.

UK Plastics Pact Annual Report 2023-24: https://www.wrap.ngo/resources/report/uk-plastics-pact-annual-report-2023-24 WRAP

WRAP Annual Report & Consolidated Accounts 2023/24: https://www.wrap.ngo/resources/report/annual-report-and-consolidated-accounts-202324 WRAP - WRAP – Reusable & Refillable Packaging

Practical guidance from WRAP on shifting toward reuse and refill models in the packaging sector.

https://www.wrap.ngo/resources/report/mainstreaming-reusable-and-refillable-packaging-uk WRAP - UK Research & Innovation – Smart Sustainable Plastic Packaging (SSPP) Challenge

This report shows innovation, scale, and carbon impact of projects in sustainable packaging in the UK.

https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/IUK-14042025-Smart-Sustainable-Plastic-Packaging-Challenge-Celebration-Report.pdf UK Research and Innovation - Carbon Trust – Briefing: Net Zero for Corporates

A concise comparison of carbon neutrality vs net zero, definitions, roles of offsets versus removals, and methodological approaches. https://www.carbontrust.com/our-work-and-impact/guides-reports-and-tools/briefing-net-zero-for-corporates Carbon Trust - Carbon Trust – Target Setting & SBTi Alignment

Carbon Trust’s perspective on aligning corporate targets to science-based pathways and what constitutes credible reduction.

Target setting: https://www.carbontrust.com/what-we-do/net-zero-transition-planning-and-delivery/target-setting Carbon Trust

SBTi / Scope 3 discussion: “SBTi series: Why long-term Scope 3 targets …” Carbon Trust - Wikipedia – PAS 2060 (for context / status)

A quick reference on PAS 2060 (Specification for demonstrating carbon neutrality) and its phase-out or update.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BSI_PAS_2060 Wikipedia